Monthly Archives: June 2016

New social media links!

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve (finally broken down and) started an Instagram account and added a link on botanicalgardening.com! It features iPhone photography and is one more way for us to communicate about gardens and our relationship with the natural world. There’s nothing (next to being there) that cures plant blindness like a fine photograph.

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve (finally broken down and) started an Instagram account and added a link on botanicalgardening.com! It features iPhone photography and is one more way for us to communicate about gardens and our relationship with the natural world. There’s nothing (next to being there) that cures plant blindness like a fine photograph.

I’m also excited to provide links to Twitter and LinkedIn to provide complete access to what I do online.

Welcome to my social circle….let me know what you think!

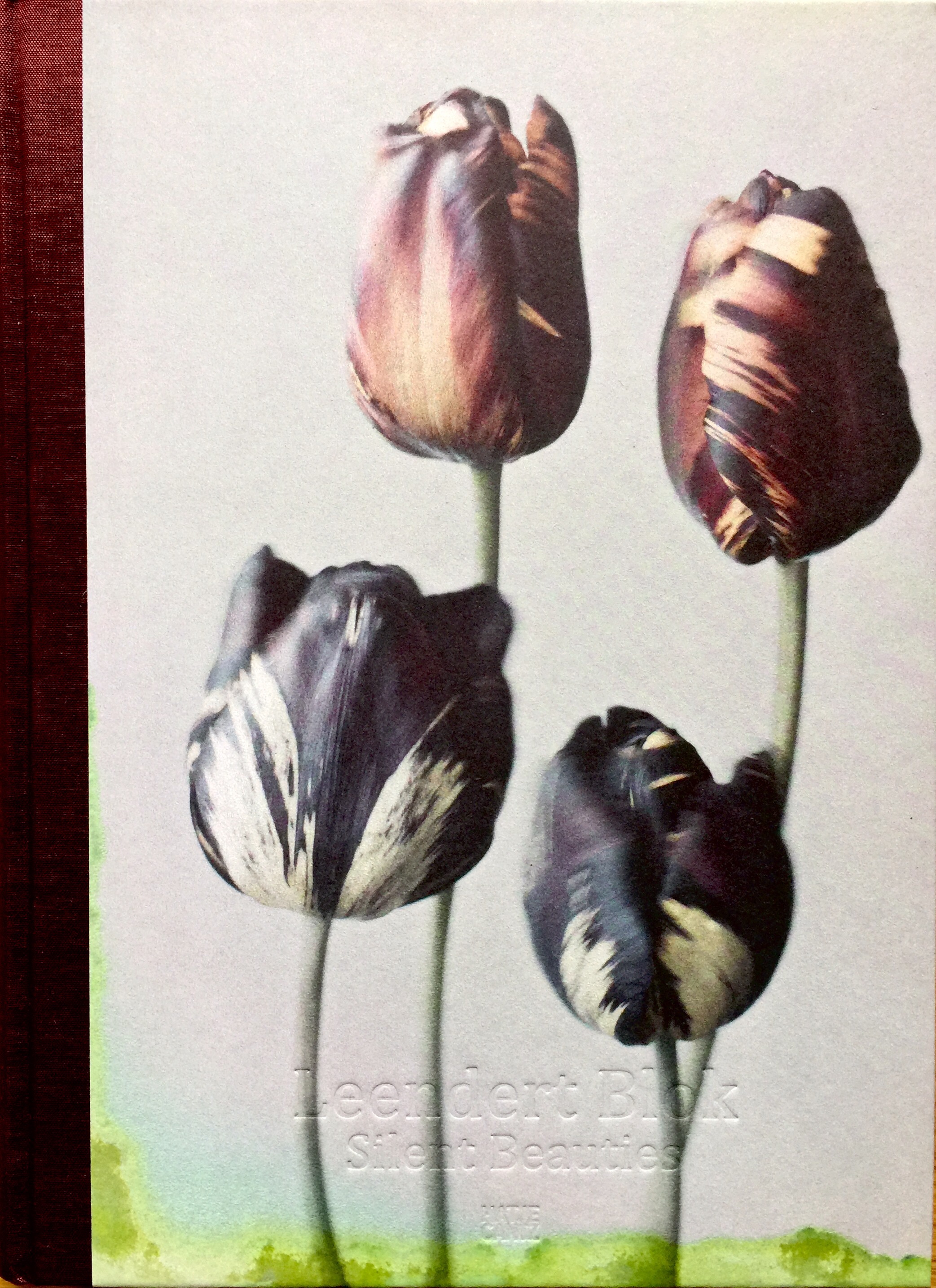

Leendert Blok: Silent Beauties–Photographs from the 1920’s

A photograph of a plant always contains a message.

–Gilles Clément (from the text)

If Clément’s statement is true, then the central message of Leendert Blok: Silent Beauties–Photographs from the 1920’s (Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, Germany, 2015) is, “We were there….”

The book examines the nascent color work of Blok (1895-1986), an early adopter of the Lumières’ Autochrome process, one of the first uses of color in photography—and the dominant process before the invention of color film. Mssr. Clément’s too-brief text and the ethereal photographs of Leendert Blok provide a fascinating glimpse of the intersection of the histories of photography and horticulture and evidence that, though unrelated, the two disciplines were advancing at the same time and grew up benefiting from each other.

It was serendipitous that color photography was developed at the same time that horticulturists began addressing market demand by developing varieties never seen in nature—large, colorful flowers resulting from plants being “manufactured” and controlled in careful breeding programs. At the same time the plant world was making plants with big, technicolor flowers the industry’s dominant paradigm, photography was venturing into the world of reproducing subjects IN color. For Blok it was a marriage made in heaven.

The link between the histories of photography and of horticulture runs deeper than Blok’s work. One of the very first books to feature color photography and color printing was, Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries, Their Practical Application. This twelve volume magnum opus is the most extensive publication of the renowned horticulturist Luther Burbank (1849–1926). The set, published in 1914-1915 contains 1260 photographs from autochrome plates.

One hundred years later, this book is the first to feature Blok’s work. During his career, his main clients were nurseries and bulb producers who used his images as catalogue visuals and marketing pieces.

Clément assumes that Blok was aware of the work of Karl Blossfeldt, (see, Karl Blossfeldt: The Complete Published Work (Hans Christian Adam, Taschen: 2008)) a contemporary who blossomed into public consciousness in his sixties after decades of using his work as teaching aids. There is no indication that the two were acquainted. Or that either knew Burbank…though they may have known his work.

As opposed to Blossfeldt, who built his own cameras to photograph the minutiae of plants– leaves, tendrils, leaf scars, cross-sections, apical stems, fern croziers, but less frequently flowers—Blok’s photographs are almost exclusively of the blooms created by horticulture.

The book showcases plates made in the 1920’s and —the pre-film portion of Blok’s career. The plates gain a measure of their appeal from the process used to create them. They carry the patina of age and their color has held well. The autochrome process was technically demanding and required slow shutter speeds. Prints tend to be grainy, giving them what has been described as “a hazy, pointillist effect.” The result is a dream-like quality still popular today—as evidenced by dozens of smart phone apps with filters to emulate the same effect.

The text by Clément focuses on Blok’s subjects, the “Silent Beauties” of the title. Between it and the very short biography of Blok, there is relatively little mention made of career (which after all spanned a far longer period than that covered by the book) and technique. More on each subject would have been welcomed.

That Blok, like Blossfeldt, was not appreciated as an artist early on is understandable as his photography was done with commerce, rather than art, in mind. The rediscovery of his oeuvre and the publishing of this early portion of it exposes his efforts to the light of day and should ensure his spot in the history of photography—and add to the lore of man’s involvement with plants.

Recent Comments