Posts By carlobal

Engineering Eden

Manipulation of the natural world is a fundamental tenet of gardening. That we do it under the guise of “improving” a situation we are presented with cannot skirt the fact that we are taking what is and making it what we want it to be. Because this may occur (more often everyday) in the context of what is already a human-altered state of affairs does not reduce the importance of what some consider an arrogant mindset.

Connecting to other disciplines, working through their thought processes and applying the lessons learned to the garden is a valuable exercise for the thinking gardener. To be sure there are those with no inclination to examine the why’s and wherefore’s, but those with interest will be able to add another layer of enjoyment to their gardens.

In this context I offer a look at a fascinating new book, Engineering Eden: The True Story of a Violent Death, a Trial, and the Fight Over Controlling Nature, by Jordan Fisher Smith (Crown Publishing, New York, 2016, $28.00).

The book is nominally about management efforts, effective and not, for black bear, grizzly bear, elk, fire, and forest in the national parks. It weaves together the stories of the national parks, a gruesome death at the jaws and paws of a bear, the subsequent trial over the parks’ management policies, and the history of the fight to control nature. In truth it goes far deeper, addressing what is often our simultaneous fear of, romantic fascination with, and desire to wring resources from, the natural. When read in the context of our management of nature through gardening, the book provides much food for thought.

It is based on a grand statement, and an even grander question. The statement was the very justification for the creation of the national parks—that some places needed to be protected because of, “…the most fundamental characteristic of human civilization: the alteration of everything we touch[ed].”

The question? In our efforts to protect and preserve, should we be guardians or gardeners? How much, in other words, should we do? Should we be guardians and simply let natural systems and processes play out their roles? Or should we actively manage to improve the chances for an outcome we deem more appropriate? How much is enough/too much?

Gardeners understand the statement. It is the essence of the activity of gardening. The questions, however, are not often addressed out loud. We take it for granted that we must be more than guardians. Even those who love native plants/gardens, prairie and/or bog gardening and restoration ecology, seldom consider whether just letting things be should be the proper course of action. Things have just gotten too out-of-hand. There is far too much water over the dam. Botanical and other public gardens grapple with this on a regular basis–but invariably default to the “management” side. Botanical gardens with “natural” areas who do NOT manage (think, trail maintenance, exotic/invasive control, tree management, prescribed fire or mowing) are vanishingly rare. We assume that what we do makes things better; moreover that it keeps things “natural.”

The decision to manage connects process to outcome. In the lawsuit at the center of Engineering Eden it was the management activity of the national parks that was called into question. Whether in parks, or in gardens, the activity that constitutes management has the potential to create liability—hence the trials that spill from ‘acts of nature’ like bear attacks, falling trees, moving water, and poisonous plants.

The mandate of the national parks was a paradox; to function as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people (to say nothing of institutional resource extraction), and at the same time “provide for preservation, from injury or spoliation, of all…natural curiosities, or wonders within said park, and retention in their natural condition.” This set up the uncomfortable bifurcation of conservation: utility vs. glory.

Well known names in the natural science, ecology and conservation fields peopled teams on either side of the divide and Smith’s recounting of the battles between the “guardians” and the “gardeners” and the evolving shifts in thought and management, were the most interesting part of the book.

The history of botanical gardens has similar arc. So much so that when the Ecological Society of America was formed in 1915 and one of its first acts was to, “express concern about the competing roles of national parks as tourist resorts and nature refuges, which, they said, had gravitated far more to accommodating visitors than preserving a biological legacy,” it could have been speaking about the traditional roles of botanical gardens as institutions of science, learning and conservation; and the current trend toward non-botanical/horticultural event venues and being pleasure parks.

Smith writes in a style and pacing familiar to readers of The New Yorker long form. He moves smoothly from essay to science writing to historical journalism and trial reportage. Through it all the Engineering Eden is a sobering look at a history that is seldom told and little known. It’s probably no accident that it debuts in the 100th anniversary year of the national park service. Hopefully the story will not be lost in the celebration.

At the end of the day, national parks ARE gardens. When Starker Leopold spoke to the Sierra Club’s Fourth Biennial Wilderness Conference in 1955 he said that wilderness areas should be managed, “to simulate original conditions as closely as possible.” (emphasis added). Smith unpacks that statement in a thought-provoking and critical way, stressing the difference between a simulation or “approximation” and “precise re-creation .” Tellingly, he writes, “…a simulation had a maker. It was not a thing in itself, but rather the product of an intention in the maker for the benefit of a viewer or user...” (emphasis added).

What Smith has just done is provide a clear and unambiguous definition of, “garden.” And Leopold’s point was that to be a guardian, you have to be a gardener.

An entire public sector bureaucracy has mushroomed to deal with our national open spaces, the resources they contain, and the conservation of the life forms and processes that inhabit them. There is no going back. By as early as the 1920’s the “balance of nature” was irretrievably broken, and now some of the elements needed to even approximate pre-settlement conditions are gone and not coming back. Smith concludes that the big questions haven’t been answered…and he argues they shouldn’t–so they get asked and discussed every time we face a decision about preserving life on earth.

The big questions playing out in our gardens are likewise unanswered. Too often they aren’t even asked. The big take-away from Engineering Eden is that they should be–and honest, respectful discussion should ensue—every time we confront decisions to be made in our most precious spaces.

Published in Public Garden!

We’re very pleased to announce that photographs from Carlo Balistrieri Photography were selected for the cover, and center spread of the American Public Garden Association’s magazine, Public Garden.

The cover image, featuring macro-detail of Zinnia flower parts, was shot outdoors from a cut-flower bouquet purchased at a local farm stand.

The center spread is a photographed of fasciated Rudbeckia flowers taken in a meadow at the Royal Botanical Gardens-Canada in Hamilton, Ontario.

In all my years of gardening/botanizing, these are perhaps the most beautiful flowers affected by fasciation that I’ve seen.And yes, this shot on the director’s page is mine as well:

…featuring one of the fabulous Bulbophyllum…this one formerly a Cirrhopetalum. Ain’t nature grand?

If you have any image needs, I’d love to discuss them with you!

New social media links!

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve (finally broken down and) started an Instagram account and added a link on botanicalgardening.com! It features iPhone photography and is one more way for us to communicate about gardens and our relationship with the natural world. There’s nothing (next to being there) that cures plant blindness like a fine photograph.

I’m pleased to announce that I’ve (finally broken down and) started an Instagram account and added a link on botanicalgardening.com! It features iPhone photography and is one more way for us to communicate about gardens and our relationship with the natural world. There’s nothing (next to being there) that cures plant blindness like a fine photograph.

I’m also excited to provide links to Twitter and LinkedIn to provide complete access to what I do online.

Welcome to my social circle….let me know what you think!

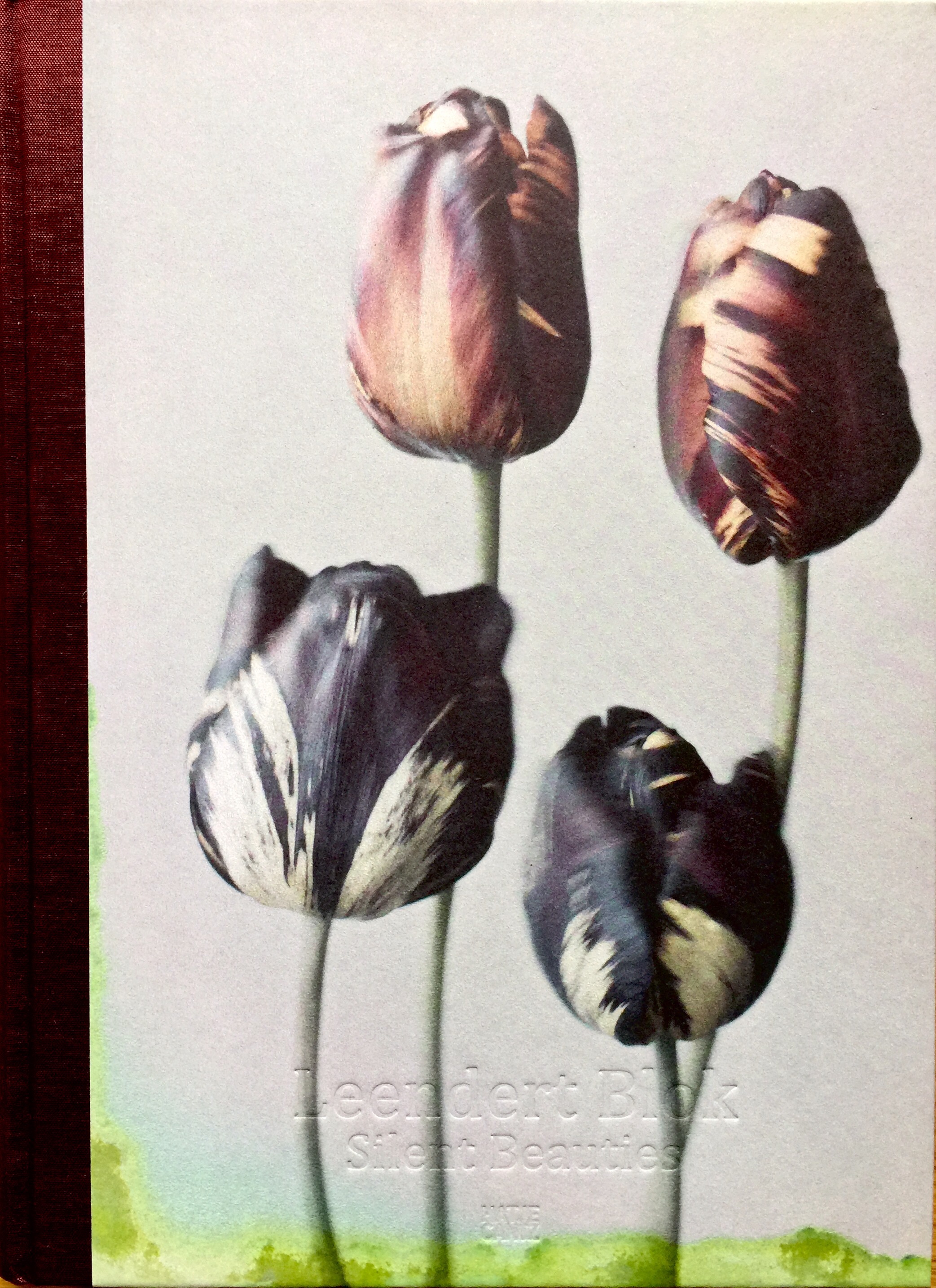

Leendert Blok: Silent Beauties–Photographs from the 1920’s

A photograph of a plant always contains a message.

–Gilles Clément (from the text)

If Clément’s statement is true, then the central message of Leendert Blok: Silent Beauties–Photographs from the 1920’s (Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, Germany, 2015) is, “We were there….”

The book examines the nascent color work of Blok (1895-1986), an early adopter of the Lumières’ Autochrome process, one of the first uses of color in photography—and the dominant process before the invention of color film. Mssr. Clément’s too-brief text and the ethereal photographs of Leendert Blok provide a fascinating glimpse of the intersection of the histories of photography and horticulture and evidence that, though unrelated, the two disciplines were advancing at the same time and grew up benefiting from each other.

It was serendipitous that color photography was developed at the same time that horticulturists began addressing market demand by developing varieties never seen in nature—large, colorful flowers resulting from plants being “manufactured” and controlled in careful breeding programs. At the same time the plant world was making plants with big, technicolor flowers the industry’s dominant paradigm, photography was venturing into the world of reproducing subjects IN color. For Blok it was a marriage made in heaven.

The link between the histories of photography and of horticulture runs deeper than Blok’s work. One of the very first books to feature color photography and color printing was, Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries, Their Practical Application. This twelve volume magnum opus is the most extensive publication of the renowned horticulturist Luther Burbank (1849–1926). The set, published in 1914-1915 contains 1260 photographs from autochrome plates.

One hundred years later, this book is the first to feature Blok’s work. During his career, his main clients were nurseries and bulb producers who used his images as catalogue visuals and marketing pieces.

Clément assumes that Blok was aware of the work of Karl Blossfeldt, (see, Karl Blossfeldt: The Complete Published Work (Hans Christian Adam, Taschen: 2008)) a contemporary who blossomed into public consciousness in his sixties after decades of using his work as teaching aids. There is no indication that the two were acquainted. Or that either knew Burbank…though they may have known his work.

As opposed to Blossfeldt, who built his own cameras to photograph the minutiae of plants– leaves, tendrils, leaf scars, cross-sections, apical stems, fern croziers, but less frequently flowers—Blok’s photographs are almost exclusively of the blooms created by horticulture.

The book showcases plates made in the 1920’s and —the pre-film portion of Blok’s career. The plates gain a measure of their appeal from the process used to create them. They carry the patina of age and their color has held well. The autochrome process was technically demanding and required slow shutter speeds. Prints tend to be grainy, giving them what has been described as “a hazy, pointillist effect.” The result is a dream-like quality still popular today—as evidenced by dozens of smart phone apps with filters to emulate the same effect.

The text by Clément focuses on Blok’s subjects, the “Silent Beauties” of the title. Between it and the very short biography of Blok, there is relatively little mention made of career (which after all spanned a far longer period than that covered by the book) and technique. More on each subject would have been welcomed.

That Blok, like Blossfeldt, was not appreciated as an artist early on is understandable as his photography was done with commerce, rather than art, in mind. The rediscovery of his oeuvre and the publishing of this early portion of it exposes his efforts to the light of day and should ensure his spot in the history of photography—and add to the lore of man’s involvement with plants.

Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Western Mediterranean

There can be no disputing that the western Mediterranean is one of the most desirable travel locations in the world. Pick a country and tourism is likely to be one of the biggest drivers of its economic engine. But a hidden wonder awaits, if only people would budge from their sun-drenched beaches, boats, cafes, shopping and museums. Though the countryside is one of the most human-impacted on earth, it retains an incredibly rich and diverse flora with many plants that can be found nowhere else.

Plumbing the depths of this treasure trove is a task that requires help and guidance. Once past the “plants as backdrop” stage, the naming of its members takes on an addictive appeal. Chris Thorogood’s Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Western Mediterranean (Kew Publishing, 2016; 640pp;. ISBN 9781842466162; Hardback) is calculated to give readers the best chance identify plants they might encounter in the region.

The flora of Europe and northern Africa is vast, particularly so in the mediterranean climate belt surrounding the great sea. This is the first time that the phytogeographic region of the western mediterranean is covered.

Thorogood, quickly becoming a 21st century Oleg Polunin, published a Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Algarve with Simon Hiscock just two years ago, here splits his consideration of eastern and western Mediterranean based on climate (which in this volume is the classic hot, dry summer/cool, wet winter we think of as “the” Mediterranean climate) and hints that a separate guide should be published for the East.

Certain classes of plants are separated from consideration here to help make the job manageable. Alpines, the flora of Macaronesia, and the mountain and desert zones of northern Africa are left for another day and other books. As it is the book covers 2400+ of the species you’re most likely to encounter—along with a tantalizing sprinkling of endemics and local rarities to keep you life-listing past your first trip to the area.

The book is a visual treat with over 1400 record photographs taken in situ and in excess of 880 line drawings to emphasis details helpful to identification in the field. This makes it a treat for the old-school, morphologically-minded amongst us, but a big nod is given to the growing importance of genetic analysis in the classification of plants as the entire volume is laid out in accordance with relationships established by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (which published its fourth major iteration just this month in the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society). Taxonomy is a moving target and readers may, consequently, encounter names with which they are unfamiliar. Including synonyms helps tie up any loose ends that may otherwise frustrate.

The bulk of the book, as is to be expected, is made up of species accounts. These are consistent with Thorogood’s prior work, and will be familiar to anyone who has experience with well done field guides. Accounts include native plants and exotics that have naturalized (e.g. the genus Agave and members of the Cactaceae family, which are seen across the region and thought by many to be native).

Don’t just flip to this section and put the book on the shelf or in a rucksack (though it’s a hefty book to put on your back!). The first 40 or so pages are packed with useful information to read before you strap on your boots. Thorogood does an wonderful job of clearly explaining classification and identification of plants, geography—pointing out great places to see wildflowers (your bucket list is going to grow…), and explaining wild flower habitats, including agricultural and disturbed lands.

No field guide is complete or perfect. Some will complain that Thorogood omits keys. His introductory pages, however, include many notate bene. This is clearly done to establish expectations, to tell readers what the book is and what it isn’t; what it contains, and what it leaves out. It’s another reason that it’s important to read these pages. On the issue of dichotomous keys for identifying plants he notes that for most people they are too much information, difficult for non-botanists to use properly and can lead to confusion.

The author is unapologetic about his extensive section on the Orobanchaceae, where you will find many species seen only in the most local floras. It is a treat, as his PhD had the biology of parasitic plants as its subject and he knows this material as well as anyone. As an aside, the family contains some of the most beautiful flowering plants you’ve never seen.

Thorogood’s guide is rigorous and easy to use. Not just a field guide, the book will appeal to gardeners—and not just those in Mediterranean climates. It may surprise readers to see both common and uncommon species that tolerate more temperate continental climate like that of the US northeast (e.g. the Helicodiceros about to bloom in my NJ garden hails from Sardinia and Corsica, yet has persisted here for years). I’ll leave it to you to find your favorites.

There are many field guides to the wild flowers of the Mediterranean. Most cover such a wide area with vastly different climates that they cannot hope to match the breadth of Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Western Mediterranean. One can only hope that the whisper of a similar work for the eastern region will be brought to fruition.

Royal Botanic Gardens–Victoria Publishes Landscape Succession Strategy to Address Climate Change

Botanical gardens everywhere are moving to deal with the challenges of climate change and its effects on the collections they steward. Policies are being developed around the world and one of the first, and most extensive, is that recently published by the Royal Botanic Gardens–Victoria for its 170 year old Melbourne Gardens.

Botanical gardens everywhere are moving to deal with the challenges of climate change and its effects on the collections they steward. Policies are being developed around the world and one of the first, and most extensive, is that recently published by the Royal Botanic Gardens–Victoria for its 170 year old Melbourne Gardens.

The document lays out the background, issues and problems, and proposes strategies and targets to be achieved. The document is forward-looking and seeks to take the gardens through the next 20 years.

Regardless of where in the world your garden is located, you have been, are being, and will continue to be impacted by climate change and the effects it has on your weather. Changes in the health of some plants are already being documented and the makeup of collections will likely change–not overnight, but certainly not on a geological time-frame.

Planning for the future has long been a task for garden executives. Master plans, strategic plans and others will all benefit from the nesting of a consideration of landscape succession within them. Keep your garden relevant and at the forefront of local, national, and international discussions of the biggest challenge of our day.

This is a must read for botanical garden professionals and environmental planners. RBGV has graciously made the document available to all at:

http://www.rbg.vic.gov.au/documents/Landscape_Succession_Strategy_lo_res.pdf

Thanks to RBGV and Melbourne….

LAST CHANCE to see NYBG’s 2016 Orchid Show: “Orchidelirium!”

Going now, aren’t you?

The High Line (Phaidon Press, 2015)

Two inches…

You need to make two inches of space on your groaning shelves to house The High Line (James Corner Field Operations, Diller, Scofidio + Renfro; Phaidon Press Inc.; New York, 2015; 452pp,; $75.00). Better yet, leave it out as evidence of your refinement and good taste, and a sure-fire conversation starter.

In its short life, the High Line—park, garden, promenade, mile-and-a-half short cut over the streets—has become an icon, its predecessors nearly forgotten as it spawns imitations and adaptations across the globe.

This beautiful book is a must-own for lovers of the park, urban renewal and gentrification (in the best sense of the word). In an amazing look “under-the-mulch” at the development of the concept, planning, design and construction of the High Line, its designers put it all on the line, sparing no secrets and adding more spice to the improbable tale of the resurrection of a feral landscape floating 30 feet above the city.

Phaidon has delivered a fine example of the book-maker’s art. The High Line has even higher production value than their offering of last year, the monumental The Gardener’s Garden. One miss was the separation of extended captions for an entire archive of historical material—necessitating continuous flipping back and forth to capture background. In light of the overall effort it’s a minor inconvenience. Beautifully put together, the physical book complements the material it contains and the care that went into designing it.

Densely visual, this five-and-a-half pounder is packed with photographs, maps, plans, construction documents and specifications, and planting plans. Many are foldout and, with the already horizontal orientation of the book, echo the narrow layout of the park itself.

It’s organized chronologically and catalogs its riches from the days before the idea of the High Line arose through planning, construction and use. Its life as a railway from 1934 to the last train in 1980 is not ignored, but it is with the creation of the Friends of the High Line in 1999 that things begin to take off. A 2004 design competition (won by the authors) starts the history of the project. This and the design process in 2005 mark the most interesting material in the book. Photographs detailing the construction process from 2006 through its three staged opening (2009, 2011, 2014) provide an incredible historical archive. It closes with reflections and observations, some expected, some not, now that the entire length of the project is open and ten years elapsed.

Light on text, its most interesting material for some will be the 28 pages of transcribed discussion—divided into three parts—between the design principals, Elizabeth Diller, James Corner, Ricardo Scofidio, Lisa Switkin and Matthew Johnson. Their personal thoughts and reflections enrich the book as they did the project. Inspired by the feral nature of the structure they encountered, they embraced a ‘keep it simple, keep it real’ mantra that belies the complications they faced. In some ways the repartee in these too few pages is more revealing than the eye-candy—a fascinating look into the designer’s mind and process. A true inside look at their work from concept, to process and through execution. It is an apt accounting of what Diller calls, “…the obsolescence of one program stimulating the invention of another…”. To round out your High Line library, put this book next to High Line: The Inside Story of New York City’s Park in the Sky, by Joshua David and Robert Hammond, founders of the Friends of the High Line. The two together provide the definitive, first-person accounts of the High Line from its creators and designers.

The High Line is a celebration of a project, “the process is the thing” thinking—and a refutation of Picasso’s famous saying, “Every act of creation is first of all an act of destruction.” It might have been easier to pull the structure down and start with a blank slate. What a shame it would have been. Instead the concept of repurposing post-industrial structures rather than erasing the past has inspired urban planners around the world. Millions of visitors a year validate the decision to celebrate what has gone before and give it new life for years to come.

The Orchid Show: Orchidelirium opens February 27 at

The New York Botanical Garden

I’m passionate about plants and gardens. In plants lies the salvation of the world. As a recent campaign by the United States Botanic Garden pointed out, “Plants are not optional.”

I talk a lot about “plant blindness”—our amazing capacity to walk right past what makes our existence possible. I talk a lot about the relevance and importance of botanical and other public gardens to our daily lives. I talk a lot about plants.

Another gray winter’s day in New York. NYBG’s conservatory has only the barest hint of what’s waiting inside….

Now we’ve got an opportunity to SHOW rather then tell, and it couldn’t be better timed. The New York Botanical Garden orchid show opens tomorrow and runs until April 17th—and you should run to see it. Leave the world-weary, winter-weary city grind behind and head for the garden.

Marc Hachadourian gets it. NYBG’s orchid expert is fond of calling orchids the “pandas of the plant world.” They excite attention, awe, and interest—inspiring sometimes extreme passions. It is our relationship with the orchid family that NYBG plumbs with its 14th edition of its show, The Orchid Show: Orchidelirium.

On the occasion of NYBG’s historic 125th anniversary, the garden looks back and celebrates the colorful (both bright AND dark, sometimes sordid) history of the orchid’s long march into our homes; first as precious, coddled rarities, and now as pot plants available at any grocery store.

Thousands of blooming plants are packed into the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory in an exhibit planned, designed, executed and interpreted by staff. Starting over a year ago with a concept and months of planning, the show took over two weeks of intense effort to install by an interdepartmental team.

Designed by NYBG’s Christian Primeau, the show promenades through the conservatory’s galleries—with plants incorporated into the permanent collections—and culminates in a splashy display guaranteed to take the chill out of winter.

This brings us full circle to the proof of the critical importance of plants and gardens to human well-being. I propose that ‘seasonal affective disorder’ (SAD) is not simply a climate related phenomenon. My theory is that SAD comes as much from lack of contact with plants and flowers as from the dreary gray of winter weather. While it may not make you delirious, The Orchid Show: Orchidelirium will certainly take the edge off SAD, drop the scales from your eyes, and reaffirm the importance and relevance of having places to go to see such spectacles. I dare you not to feel better after your visit….

The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY; show dates: February 27-April 17, 2016; visit www.nybg.org for ticket information and times.

Remote posting? You bet!

I’m late to to the game, but I’m back! Both BotanicalGardening.com and CarloBalistrieri.com have been reimagined AND have remote posting capabilities. I could be IN Montauk with these Nipponanthemum nipponicum and regaling you with my musings (yes they’re Montauk Daisies…but what a great formal name!). Stay tuned…the sky’s the limit.

I’m late to to the game, but I’m back! Both BotanicalGardening.com and CarloBalistrieri.com have been reimagined AND have remote posting capabilities. I could be IN Montauk with these Nipponanthemum nipponicum and regaling you with my musings (yes they’re Montauk Daisies…but what a great formal name!). Stay tuned…the sky’s the limit.

Recent Comments