Posts in Category: Book Review

Review: The Planthunter: Truth, Beauty, Chaos and Plants

(Georgina Reid, with Daniel Shipp (photographer)

Timber Press, Portland, 2019; $40.00US First published as ‘book of the month’ by the North American Rock Garden Society at www.nargs.org)

There are a few things you need to know about this book.

It is not a book about gardening. You will not learn how to sow seeds for the 23rd time. You will not learn how to plant a rose for the 37th time. You will not learn how to properly prune a shrub for the 53rd time.

Nor is this a book about plants. You will not be shelving your 181st list of plants for the garden. You will not be sussing zones or sorting conflicting information on the same plant.

We’ve seen other “planthunter” books. This is not them. There are no machete-wielding bushwhackers here.

Finally, this is not a book about manicured gardens maintained by paid staffers to within an inch of their lives. There is no page after glossy page of not-a-leaf-out-of-place grandeur.

We can’t resist such books. We all have shelves groaning with these books.

This book celebrates people who grow things. You will meet two dozen gardeners from 3 foreign countries: Australia, New Zealand, and California. There are few names you will recognize. But they are people like us. They get dirty. And each of them is extraordinary.

It is a visit to the potting sheds of people who garden, and think about the act of gardening. Moreover it is a walk with them through their gardens, which are often less than pristine–but frankly, a whole lot more like ours than what is seen in other books. These gardens are lived in.

After a steady diet of New England gardens and the euro-centricity that we can’t seem to escape (there IS a whole, wide world of gardens out there…), it was revelatory to see the similarities and differences in gardens from the other side of the planet.

There are no captions on the plentiful photographs, but they are hardly necessary. There isn’t a lot of fluff in the text either. As fans of the author’s online publication “The Planthunter” are aware, she is a seeker, an asker of questions, and an over-the-garden-fence kind of communicator.

This is a book for the thinking gardener. It is itself thoughtful, and beautifully designed. It is calculated to get you thinking about your garden and your gardening. It is a love letter to gardeners, a paean to grubbers in the dirt.

Gods, Wasps and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees

In a jam for a late holiday gift? Step away from that figgy pudding and consider…the fig. Gods, Wasps and Stranglers: The Secret History and Redemptive Future of Fig Trees, by Mike Shanahan (Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT, 2016) is a short, fascinating read that delves into the history—natural and cultural—of Ficus and will leave you with a new appreciation of the genus and its place in the world.

Shanahan, a rain-forest ecologist, was motivated to write this book by three things: the importance of fig trees to tropical ecology, the influence of the genus on human culture, and his conclusion that we are destroying the first while forgetting the second. The kind of guy you’d like to sit down to coffee with, Shanahan is at ease with his subject and has clearly done his homework.

While he covers a many angles on his amble through the world of figs (which make for some of the best reading), this is a book with a message. The real reason for this book is to make recent research accessible to the masses, and the fantastic account of the “framework species approach” using Ficus species to jump-start forest regeneration in even the most degraded former forests, will have you running into the rabbit-hole of sources Shanahan provides and digging deeper. The imp lications, as well as the current research and methodology, are astounding—and reason enough to pick up this volume.

lications, as well as the current research and methodology, are astounding—and reason enough to pick up this volume.

Along the way, Shanahan makes a couple of questionable assertions. He does admit to it being arguable that “no other group of plants holds as much ecological importance, evolutionary interest and cultural value,” but missed the boat when he says that figs became “the most varied group of plants on the planet.” A cursory check reveals at least 30 genera of flowering plants with more species than Ficus.

And…looking for flowers in a fig tree is a fruitless quest (pun intended). While Shanahan acknowledges this and expounds on the cultural references that stem from the fact, he misses the opportunity to enlighten readers that a fig is not a true fruit but a syconium…an inflorescence formed by an enlarged, fleshy stem with many flowers and their ovaries inside. Only when it’s been fertilized and contains seed will it conform to our standard definition of fruit.

Ironically, though he states that “every one of the 750 plus species of Ficus species is pollinated by one or more tiny wasps,” the great majority of figs we eat come from Ficus carica and its dozens of cultivars grown around the world—a species that has done away with the necessity of having its own pollinating wasp and is able to make fruit on its own. This miracle of parthenogenesis (“virgin creation”) is what made it possible for the production of figs to move from forest to farm, tropics to temperate climates, and toyour backyard.

And therein lies my biggest beef with Shanahan’s book. While I’m certain its because of his emphasis on the seeded Ficus as forest regeneration catalysts, there’s a missing chapter in this book and it’s the story of Ficus carica, one of the most important figs to humans. Far beyond the figs we use to adorn our gardens and homes, this one makes food. A good, healthy food. I would have loved for this tale to be told. The discovery of a fig that doesn’t need fertilization by a specific wasp to fruit, its cultivation early in human history, its subsequent movement around the world, and its widespread cultivation today, is a bio-cultural marvel. Perhaps it’s another book….

Stylistically Shanahan keeps the book chatty, informal and readable. This has obvious pluses, but means that certain pieces of information get glossed over and lose depth—and that a few breathless exclamations creep in. This may be the source of some of my quibbles. This is a man, however, clearly besotted by his subject and he deserves to be heard. What I got was great…but I wanted more.

If you, like the good citizens of Athens in the time of Theophrastus, are philosykos (lovers of figs) this book is a great introduction to an amazing genus of plants, known to many—yet largely, until now, unknown.

Planting Design for Dry Gardens: Beautiful, resilient groundcovers for terraces, paved areas, gravel and other alternatives to the lawn

For some gardeners “turf is wasted space” is an approach to gardening, Others struggle to create and maintain a perfect sward of green against all odds. A final group balances the two but tries to grow in many different ways. For every group, Olivier Filippi has offered up a wondrous selection of alternatives for lawns–though his ideas are valuable for far more than just lawn replacement. Planting Design for Dry Gardens: Beautiful, resilient groundcovers for terraces, paved areas, gravel and other alternatives to the lawn, (Filbert Press, 2016), is his latest book and should disabuse lawn lovers of their notions, cheer conflicted growers of grass mono-cultures, and deeply satisfy lovers of diversity in plants and planting schemes. Add to that its extraordinarily timeliness given the ever more serious concerns about water and you’ve got a book for every gardener to savor and enjoy.

As hinted above, it is important not to get hung up on references to lawn and its alternatives. This is an important book for the way it processes ideas about gardening. Reading between the lines you get a feel for Filippi’s method. He is a thoughtful gardener. Decades of growing plants in and for Mediterranean climates has infused him with knowledge about the plants, what they can do, and how they can be used. Extensive exploration and experimentation have brought him to the forefront of the Mediterranean garden world.

Planting Design for Dry Gardens is a gift from one gardener to another. Reading it is like spending a month of Sundays in the Filippi garden with he, his wife Clara, and more than a few bottles of Bordeaux. The best gardening books do more than ‘report’ information, they share personal experience and hard-won knowledge. On this score Filippi succeeds in spades.

This is a beautiful, large format, English language (with an outstanding translation by Caroline Harbouri) version of a 2011 French publication. It’s Filippi’s second major book, following his equally wonderful, The Dry Gardening Handbook: Plants and Practices for a Changing Climate, published in 2008. Ever since reading that book, I’ve wanted to visit the author’s garden and Planting Design is as close as you can get without a ticket to France.

The book has a Mediterranean focus but will be useful to anyone seeking to avoid the high maintenance that comes with an impeccable lawn. An impressive range of plants is discussed (more later) and everyone will recognize old favorites no matter where you garden. The more adventurous among us will close the book only after constructing a lust-list of plant material to try in our (often not very Mediterranean at all) gardens..

The book has a Mediterranean focus but will be useful to anyone seeking to avoid the high maintenance that comes with an impeccable lawn. An impressive range of plants is discussed (more later) and everyone will recognize old favorites no matter where you garden. The more adventurous among us will close the book only after constructing a lust-list of plant material to try in our (often not very Mediterranean at all) gardens..

It begins with a fascinating discussion of how we got where we are vis-a-vis lawns, including where the word came from, how the practice arose, where it’s taken us, and what alternatives to grass exist. Most surprising here is the relatively recent and extraordinary influence the English lawn has had on the Mediterranean region (which already had a centuries-long history of magnificent gardens), despite the absurdity of the work it takes to establish and maintain turf in a place it does not want to grow. Filippi’s charge is to relearn how to garden sustainably in a hot, dry summer/cool, wet winter climate—and turn away from the professional-gardener-as-plumber situation in which many find themselves. Given the struggles faced by those growing lawn in the Mediterranean climate, it’s surprising that Filippi’s alternatives haven’t been de rigueur for some time.

The entire scenario is reminiscent of the lawn craze in the American Southwest and the subsequent evolution of thinking that resulted in the ongoing return of arid-land gardens in their place. There are no two better examples of working with what you have, rather than stretching for something only attainable at great effort and expense. It appears we simply have to go through it before we can come out the other end.

Readers will recognize many rock garden practices and plants in Filippi’s advice. The book moves beyond, Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden, an English and seasonal approach, and books on xerophytic plants and their use, to explore the environmental implications of the garden–a habitat approach based on projected human use of space that makes great sense.

Far from an anti-lawn manifesto, Filippi urges a move toward gardens that respect place, climate and resources. To get there he examines the ecological properties, strategies and adaptations of a variety of plant communities. Drawing his inspiration from travels throughout the Mediterranean region, he discusses several alternative plant communities moving ever further from turf with graduated levels of use. Wild lawn, steppe, gravel gardens, stone surfaces like terraces, paths, steps, perennial/shrub combinations, wild fringes with pioneer plants, and flowering meadows with their attendant advantages, disadvantages, and plants are all discussed and illustrated with the author’s beautiful images of his own garden, other gardens, and plants in the wild.

Filippi discusses the pros and cons of each plant community and how each might contribute to a harmonious whole. Rather than provide a prescription for specific concerns, he shares his thoughts and concludes that it’s “…up to you to find the option best for your particular situation.” So much information is shared that this never feels like the cop-out it might from another source.

Care for a dry garden is a bit different from what you might be used to. Planting and maintaining each of his styles is covered, with special attention paid to water management, which is, after all, the elephant between the covers. While all of Filippi’s alternatives have significantly lower water needs than most gardens, it was interesting to note his comments on the distinction between providing the water necessary for the community of plants to conduct its natural cycle (which may include dormancy and a ‘yellow/brown’ season) versus what it takes to live up to the gardener’s expectations—which might include watering in summer to overcome the natural tendency to drop leaves.

Every gardener wants to talk plants and Filippi does not disappoint. He includes a collection of plant descriptions packed with personal observation and including information not always found in such compilations. Sprinkled among the many plants you will not have heard of are garden standbys—here discussed as they are in their home haunts. A man after my own heart, Filippi makes a quiet plea for diversity…more species, more contrasts, more advantages, and an insurance policy against the failure of a less diverse planting.

Neither does he avoid controversy. The book contains an impressively reasoned look at ‘invasives’ and the definitional, theoretical, biogeographical and temporal confusion that swirls around the issue. Tucked into the plant list are species like Glechoma, Hederacea, Plantago, Prunella, and Taraxacum that many consider dastardly weeds—if not invasives to be avoided at all costs. In addition there are new finds, like Phyla canascens which, despite its ground covering prowess, would be welcome in my garden. Give his views a chance—and read the sources he provides—then, as above, decide what’s right for you. Some weeds are gardeners best allies.

A perfect lawn, notes Filippi, is always on the verge of reverting to a mixed grassland. Here are well researched, thoughtful alternative plantings to eliminate that pain. All that really needs to change is the gardener’s mind and approach.

The Monster in the Garden: The Grotesque and the Gigantic in Renaissance Landscape Design

“All modern tourists…are heirs to an animistic myth.” —Fabio Barry

Giants and monsters and grotesques, oh my! It’s a minor miracle that people don’t run screaming in fright from Renaissance gardens. Why, you might ask, are they so packed with statues that inspire dread: monsters giants, mythical creatures—hybrid and imaginary—and grotesques of every kind? The Monster in the Garden: The Grotesque and the Gigantic in Renaissance Landscape Design, by Luke Morgan (University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 2016) seeks to answer this question and more in an erudite synthesis of history, theory and cultural sociology.

Make no mistake. This is a serious, thoughtful and thought provoking book. It is academic (as befits its publisher), and not the typical fare for lovers of garden books. [Fair warning: those who are put off by sentences like…“The Sacro Bosco that emerges from this chapter is certainly unusual, but it is not, as has sometimes been argued, a bizarre oddity or aporeitic outlier constructed in a personal idiolect analogous perhaps to that of the Hyponerotomachia in literature,” may have a difficult time negotiating Morgan’s path to enlightenment] And yet, for those who think about why they do what they do in their gardens, and perhaps even more for those who do not; for people fascinated by the history of gardens and for all who seek meaning and substance, it is a journey worth taking.

The Renaissance, considered the link between the Middle Ages and modern times, is usually thought of as the re-ascendancy of humanism and a “man is the measure of all things” mentality. Conversely it is sometimes considered a pessimistic age full of nostalgia for classical antiquity. Both views are useful in the search for an explanation of the monstrous and grotesque.

Morgan runs down many avenues in his search for monster meaning. How gardens are received and experienced by visitors is a central theme. Whether the concept of the monster is as a natural wonder or marvel, a dread omen, or both, is an important element of the analysis.

He creates a new theory of Renaissance landscape design—that these ubiquitous monsters are not merely incidental adornment of 16th century gardens, but essential features. Giants and grotesques, he posits, are ciphers for the contemporary anxieties of the Renaissance. Morgan is fond of dichotomies. Borrowing one from Leonardo da Vinci, he examines the connection between fear and desire. The presence of these creatures in gardens inspires dread by suggesting the threatening aspect of the unknown, while at the same time creating a desire to know whether wondrous things might be found inside. Morgan argues that as early modern gardens are microcosmic representations of the world outside its walls, the ‘dark’ side of life must necessarily intrude into the idyllic.

Another duality is the interplay of nature’s kindness and cruelty. The presence of horror in a place of pleasure could be seen as a contemporaneous expression of these two sides of the natural world—and a coming to grips with its impact on the people of the day.

Another duality is the interplay of nature’s kindness and cruelty. The presence of horror in a place of pleasure could be seen as a contemporaneous expression of these two sides of the natural world—and a coming to grips with its impact on the people of the day.

Morgan addresses the taming of nature in the Renaissance garden and points out that, “…the mind and will of the designer or ‘garden builder’ has a transformative effect on the elemental latency and formlessness of nature.” That nature would submit to and be improved by art is not a new idea, but that the unknown could be made knowable, dread of it tempered by making it seen, may be a new twist. Perhaps the monsters are there to remove fear. If the monsters aren’t present…they are hidden. If they are hidden, fear is heightened.

Another view Morgan visits is a twist on the definition of “sublime.” Monsters create experiences of wonder and amazement—mystical episodes of rapture—including horror and fear. Not unlike carnival rides and horror movies, this resulted in ”ecstatic helplessness in the face of the unfathomable.” In the Renaissance garden it means the creation of pleasurable fear or dread in the face of great beauty.

There are hints of yet another duality, a ‘theory of opposites.’ This is the idea that grotesque images make the beauty of the garden more complete, that horror enhances the experience of joy and happiness. Monsters and giants might be necessary to the “idyll” of the garden since “the monstrous is only monstrous in relation to a consensual but artificial norm.” Not only do the figures suggest untamed, unknowable nature and render it somewhat comprehensible, they heighten the experience of the rest of the garden. The “dramatic duality between pleasure and dread” is equally well served by this theory.

It’s not a new thought. Jacopo Bonfadio, often credited with the concept of a “third nature,” suggested in 1541 that the interaction of art and nature could produce more extraordinary effects than either on its own. By extension Morgan’s various dichotomies and dualities would have enhanced the experience of the garden by its visitors.He suggests that the grotesque and monstrous are, “…the necessary shadow of the classical, in the absence of which neither has any definition.” Gardens, he points out, are better equipped to express this duality than any other early modern artistic medium.

There is little or no contemporary history of garden reception (by visitors) or written context for the inclusion of monstrous/grotesque elements in Renaissance gardens. As a result, contemporary attitudes need to be reconstructed to assess meaning. That means peering into other cultural artifacts of the era and extrapolating meaning to the garden and its interpretation.

By necessity, therefore, the book is inconclusive about why the grotesque and gigantic, the monsters, colossi, hybrids and ruins show up in nearly all Renaissance gardens. Morgan admits to other possibilities of meaning and significance in the garden. Theories and interpretations abound. Not surprisingly, after all his analysis Morgan concludes that gardens should be seen as, “…accommodating, indeed promoting, inconsistency without resolution.” Reception, and by extension meaning, should be thought of as “…a subjective, idiosyncratic, tendentious, partial, magpie-like, fallible and biased.”

Many a modern garden contains classical statuary in imitation of the gardens of the Renaissance. Not unlike the mystery of early modern gardens what is missing, is why. In what context are they included? Is it enough that it was seen in an important garden somewhere else? Is there something innate, buried deep in the subconscious, that compels us to include symbols of fear and dread in our most private, enchanted spaces? Perhaps it is Barry’s “animistic myth” coming to the fore. Likely, as with the Renaissance garden experience, there is no definitive answer.

It is curious that no detour was taken to discuss why these elements continue to be included in gardens today, or whether our fascination with monstrous plants, topiary and even garden gnomes, is related. Furthermore, what their modern day context might be. Perhaps a “frisson of pleasurable dread,” even if unconsciously realized, is just as important today as it was 500 years ago.

The Blue Garden: Recapturing an Iconic Newport Landscape

Once upon a time, there was a garden. It was a fine garden and wonderful, magical things happened there. It was born of desire, passion, compromise and great care. It was known far and wide. The garden was blue.

No one knew why the garden was blue. It was not a sad, morose, or melancholy place. Was it a love’s eyes? The tiles? The ocean, sky, or part of the allegorical story the landscape was designed to tell? It’s a mystery even today.

Sprites, faeries, nymphs and satyrs made the garden home. Mermaids plied the waters of its pools and people from all over the world visited to enjoy its beauty and enchantment. For years they drank in its pleasures.

Then, somehow, the magic was lost. After decades of loving attention to its every need, the blue garden fell on hard times–the whole country fell on hard times. Some people died; others lost the will and/or means to continue caring for a place that would not survive without it.

Nature began her march on the blue garden. Beds filled in and grew over; trees freed of their regular pruning, grew luxuriantly. A slow accretion of dead plant material and new soil crept over the hardscape. Soon it was nearly unrecognizable. Grandeurs and splendors sunk under nature’s encroaching mantle.

Yet someone saw.

Someone saw hints and then the bones of the blue garden and had an inkling of its history and glorious past. Someone who wanted to see the garden as it once was, to recreate the magic. Someone who knew the kind of people, skills, and resources it would take to bring the garden back from its humusy grave.

And that someone did something about it.

“Blue color,” wrote art critic John Ruskin in the 1800s, “is everlastingly appointed by the Deity to be a source of delight.” Whether in his camp or not, it is to everyone’s everlasting delight that the blue garden has been reborn.

Now the whole story is being told. The Blue Garden: Recapturing an Iconic Newport Landscape (by,

Now the whole story is being told. The Blue Garden: Recapturing an Iconic Newport Landscape (by,

Arleyn A. Levee, Redwood Library & Athenaeum, Newport, RI 2016, (208 pages plus DVD, $65.00USD)) is destined to become a treasured volume of garden history. Meticulously and exhaustively researched, it is an eye-opening overview of the history of the iconic garden of Harriet Parsons James and her husband Arthur Curtiss James, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and Olmsted Brothers. The book’s true importance and lasting contribution, however, may come from the template it provides others. It is a blueprint for how to document such a history–and a clarion call, of sorts, for gardeners, landscape architects and others, to save plans, correspondence and other written and digital materials; to photograph the details and the overall effect, the process, the before and the after.

Every garden is remarkable. Every garden tells a story–some are quotidian–a tale of sustained, persistent effort; organic, undesigned. Others are as remarkable as the gardens they document. The story of the Blue Garden is one of the latter. Conceived, planned, executed, loved and lost; then resurrected and restored, and finally, documented by a remarkable group of motivated, resourceful individuals spanning a century from the original Olmsted plans on paper to 21st century digital video footage captured by an overhead drone.

The Blue Garden: Recapturing an Iconic Newport Landscape is the story of a garden taken back from nature who, as is her wont, prevails over any man-built project, given enough time and a modicum of neglect or changed circumstances. It is an instructive and inspiring tale.

The garden dates to the early 20th century and is notable, among other things, for being hewn, nay, blasted out of the rock that surrounds it. Its Italianate formality created a striking juxtaposition to the natural landscape ringing it. Its site and form is an allegory for the struggle between man and nature–even more so when the story of its original construction and its recent restoration is told.

The bulk of the book is history. Extensive background information on the James family and its history helps to set the scene. Copious evidence of the planning and design of the entire property and its garden are shared. Reams of correspondence and documentation were preserved, much of it by the Olmsted firm, but by other parties as well. Ironically, despite the wealth of information, there is no written evidence of why it was to be a blue garden. Speculation included the color of Harriet’s eyes, the union of sky, earth and water, and other flights of fancy—but by 1911, she knew what she wanted.: blue and blue/purple–no magenta purple–with some yellow and white. No pink, no red. AND it needed to be in bloom by mid-summer.

Early Olmsted concerns that creating a formal garden on the estate would be incongruous with its rugged land-forms and injurious to an overall plan to protect and enhance the natural environment. Sensitivity to the thoroughly modern-day issues of the protection of native plants and removal of exotics (despite the fact that plenty of exotics were used in plantings) were expressed. In the end, however, the owner’s wishes won out, accommodations were made and a garden was built.

This is not just a story about a garden.There are many layers to this book. One of the most fascinating is an in-depth look at the relationship between owner and designer/builder as it, and the thoughts and ideas it spawned, evolved over time.The Jameses were active, engaged owners and the book reveals the not-always-delicate interplay between them and the designers. Disagreements, discussions and compromises are frankly exposed, along with failures in the garden that needed to be addressed–and were.

The decline of the garden is covered quickly and more detail of this part if it’s history would have been a constructive lesson in garden building, management and long-term sustainability. But in the end, this is a book about rebirth.

There is a brief, but interesting look at garden preservation which, again, might have been enlarged. The recent clamor over the threatened destruction of the Russell Page garden at The Frick Collection, a museum in New York City (the garden was saved) and other examples too numerous to mention, point out the importance of the work of saving significant gardens and, given the success of the Blue Garden restoration, a second lesson might have been taught.

Lost for decades, the Blue Garden was rediscovered in the mid 1960s-70s with some work done in the 80s. It wasn’t until it was brought to the attention of, and purchased by, philanthropist Dorrance Hamilton,that restoration began in earnest. Far more Lazarus than a Phoenix–rising as it did with at the hand of another rather than independently from the ashes–the Blue Garden rescue and restoration began in 2012 and concluded with a grand re-opening in 2014. As can be seen by the book’s remarkable photos, the restoration accomplished its purpose dramatically, bringing back the look and feel of James’ garden and milieu, without becoming a slavish re-creation.

The final chapter is about the ”new era,” covering restoration and the future. At 20 pages, (barely more than the end notes) it is the third and final part of the book where more would have been appreciated. In particular, a more in-depth discussion of the plans for the future of the garden and its significance as a source of education and inspiration for garden lovers would have been a great way to conclude the story.

There is a wonderfully done companion DVD documenting the process visually. It helps fill the gap, but given the amount of thought and effort that went into the restoration and the preparation of the book about it, it’s surprising that more is not provided on these important questions. Perhaps it’s all too fresh.

As if to fend off the further efforts of nature, the book is beautifully produced of heavy, matte paper designed to withstand the ravages of time. The bundled DVD documentary, Building the Blue Garden, is a wonderful look at the restoration process including interviews with the principals and a detailed look at the incredible effort and passion dedicated to the project. It is sure to delight readers of the book.

Vision, enduring commitment and significant resources are required to pull something like this off. The Blue Garden was lucky to find its angel investor. The well known, variously attributed quote,“This is what God would do if he had the money,” immediately springs to mind when the story of the original construction of the garden is read—and makes a curtain call after documentation of the restoration, in written and visual form, is assessed. We are fortunate to have this project and its story spelled out in such detail.

Writing of the Masque of the Blue Garden, the grand fête arranged by Harriet Parsons James to dedicate her garden on August 15, 1913, an unidentified reporter says, “(A) fairy demesnes of gleaming white arcades, fountains and luxuriant bloom which the taste and inventive genius of artists supply to millionaires nowadays over night…We are entirely too progressive to wait centuries for anything, so our gardens like our pedigrees are made up out of books and the Jameses have a perfectly good garden that entrances the casual eye and will last them their lifetime. After that, who cares?”

Someone cared, the garden was spared, and now, it is shared.

The Blue Garden is available at:

Redwood Library and Athenaeum

50 Bellevue Avenue

Newport, RI 02840

and online at the Redwood Bookshop, https://squareup.com/store/redwood-library-and-athenaeum

Luciano Giubbilei: The Art of Making Gardens

Luciano Giubbilei: The Art of Making Gardens (Merrell Publishers, London and New York, 2016, $70) is a beautiful book; and a profound expression of garden thought. It’s also confusing. Is it a beautiful coffee table ‘art book’ with pretensions of being a gardening book; an artistic gardening book, an essay, or a gardening book that is really a confessional. At the end of the day, it is all…and none…of the above.

The difficulty comes from its title, and the promise that ‘the art of making gardens’ will illuminate, elucidate and confer upon its readers the secrets they long to have explained. There are dozens of authors and even more books, from every part of the world, that better plumb the depths of “making gardens.” Truly that is not what this book is about. Giubbilei acknowledges as much, saying, ‘It’s not a ‘how to’ book—I’m not trying to teach anyone anything….”

The real story of Luciano Giubbilei: The Art of Making Gardens is the highly personal odyssey of a celebrated garden designer; the evolution of his thoughts on designing gardens to a higher plane.

This is a book about a ‘road-to-Damascus’ moment for a garden designer who has never had a garden of his own; an award-winner whose most famous work is best characterized as classically informed modern, monochromatic, and Italian. Green (”…lack of colour is important.”). Clean. Geometric. In his own words, “masculine.”

This is a book about a ‘road-to-Damascus’ moment for a garden designer who has never had a garden of his own; an award-winner whose most famous work is best characterized as classically informed modern, monochromatic, and Italian. Green (”…lack of colour is important.”). Clean. Geometric. In his own words, “masculine.”

It is a rare, introspective look at a successful designer, accumulating commissions and accolades, who is vaguely uneasy, dissatisfied, and convinced, finally, that something is missing. “On paper everything looked good, but inside I was struggling to find the meaning in what I was doing,” he writes. THIS is the “why” of this book and the story for which you’ll want to read it.

This book is about a search, a quest, a personal journey. It’s a documentation of an evolving creative process and approach to garden making. The text is warm, vulnerable and honest—extraordinarily personal. It is a frank baring of Giubbilei’s thoughts and soul, coming from a compelling need to move his artistry beyond what made him successful–and a growing recognition of that which he did not know.

Dogged by nagging thoughts, he consults Fergus Garrett, of Great Dixter in England, and begins a dialogue that leads to a relationship—and a plot of land—at the garden. There he begins what could be described as a high-level internship, to search for that missing element, and learn about plants and their garden uses. At Great Dixter he gains a new appreciation of the relationship between design and horticulture, becomes enamored of flowers and colors beyond green. He grows, and he grows. Three years later ascends the mountain at Chelsea garnering gold and best in show.

The book has three major sections. The first is about Great Dixter, what brought him there, his experience with the place and its people, and the inspiration he drew from his time in the garden. Following this is a discussion of the new aesthetic emerging in Guibbilei’s work using his 2014 Chelsea garden as an example. Finally, he discusses craft and collaboration; one of the key components of his new approach: using experts in horticulture and allied fields to fill in the gaps in his expertise, commissioning original works of art, and designing and manufacturing bespoke garden furniture with which to dress his gardens.

There are a few shortcomings to this book besides the initial confusion about its central thread. They occur before, during and after Guibbilei’s ‘aha’ moment.

Before: The book fails to place Giubbilei’s preexisting work in context so that the transformation in his thinking can be seen. There are no examples of his earlier work and thus the book misses the chance to visually establish the condition precedent to the entire story arc. This could be a business decision based on the republication by the publisher just last year of, The Gardens of Luciano Giubbilei, which does cover the early gardens, but if that’s the case, Merrell does a disservice to readers of this book. The impact of his evolved thinking is diluted as a result.

During: With all due respect to the iconic garden and its people, the book spends too much time on Great Dixter. We know it, we love it and we revere it. Pages could have been saved for the early work or the post Chelsea oeuvre. In addition, the over-attention paid Great Dixter is curiously dark, brooding and off-season (the better to show garden-making, I suppose)—the very antithesis of what it is known for.

After: Post-awakening the book misses in the same fashion it did with Giubbilei’s early work. We are left only with Chelsea 2014, gold medal and best in show, but a competition garden. There is no indication of how his new thinking informs (or not) his current work. Not a single commission or project is shared and, consequently, no indication of whether his new ideas were a passing fancy or continue to influence what he does.

Physically, the book contains copious amounts of white space—and nearly 30 pages either completely blank, or containing just a caption. Given what was left out, these could have been employed to stronger effect.

While most photographs have some sort of caption, there are likely to be readers disappointed with captions that don’t identify the elements of the attached image and/or pages and images with no captions at all. A pure art book might get by with anonymous visuals, but a hybrid—even an elegant one—loses a little if you don’t know what you’re looking at. And a garden book is often measured by its captions.

Buy this book. But buy it for what it is, not what it says it is…. “Passion, patience and love are what counts, even if your garden is just a single pot,” writes Giubbilei. He brings those three virtues to this book in spades. Since they are at the core of his epiphany, they are central to the real message of his book.

Engineering Eden

Manipulation of the natural world is a fundamental tenet of gardening. That we do it under the guise of “improving” a situation we are presented with cannot skirt the fact that we are taking what is and making it what we want it to be. Because this may occur (more often everyday) in the context of what is already a human-altered state of affairs does not reduce the importance of what some consider an arrogant mindset.

Connecting to other disciplines, working through their thought processes and applying the lessons learned to the garden is a valuable exercise for the thinking gardener. To be sure there are those with no inclination to examine the why’s and wherefore’s, but those with interest will be able to add another layer of enjoyment to their gardens.

In this context I offer a look at a fascinating new book, Engineering Eden: The True Story of a Violent Death, a Trial, and the Fight Over Controlling Nature, by Jordan Fisher Smith (Crown Publishing, New York, 2016, $28.00).

The book is nominally about management efforts, effective and not, for black bear, grizzly bear, elk, fire, and forest in the national parks. It weaves together the stories of the national parks, a gruesome death at the jaws and paws of a bear, the subsequent trial over the parks’ management policies, and the history of the fight to control nature. In truth it goes far deeper, addressing what is often our simultaneous fear of, romantic fascination with, and desire to wring resources from, the natural. When read in the context of our management of nature through gardening, the book provides much food for thought.

It is based on a grand statement, and an even grander question. The statement was the very justification for the creation of the national parks—that some places needed to be protected because of, “…the most fundamental characteristic of human civilization: the alteration of everything we touch[ed].”

The question? In our efforts to protect and preserve, should we be guardians or gardeners? How much, in other words, should we do? Should we be guardians and simply let natural systems and processes play out their roles? Or should we actively manage to improve the chances for an outcome we deem more appropriate? How much is enough/too much?

Gardeners understand the statement. It is the essence of the activity of gardening. The questions, however, are not often addressed out loud. We take it for granted that we must be more than guardians. Even those who love native plants/gardens, prairie and/or bog gardening and restoration ecology, seldom consider whether just letting things be should be the proper course of action. Things have just gotten too out-of-hand. There is far too much water over the dam. Botanical and other public gardens grapple with this on a regular basis–but invariably default to the “management” side. Botanical gardens with “natural” areas who do NOT manage (think, trail maintenance, exotic/invasive control, tree management, prescribed fire or mowing) are vanishingly rare. We assume that what we do makes things better; moreover that it keeps things “natural.”

The decision to manage connects process to outcome. In the lawsuit at the center of Engineering Eden it was the management activity of the national parks that was called into question. Whether in parks, or in gardens, the activity that constitutes management has the potential to create liability—hence the trials that spill from ‘acts of nature’ like bear attacks, falling trees, moving water, and poisonous plants.

The mandate of the national parks was a paradox; to function as a public park or pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people (to say nothing of institutional resource extraction), and at the same time “provide for preservation, from injury or spoliation, of all…natural curiosities, or wonders within said park, and retention in their natural condition.” This set up the uncomfortable bifurcation of conservation: utility vs. glory.

Well known names in the natural science, ecology and conservation fields peopled teams on either side of the divide and Smith’s recounting of the battles between the “guardians” and the “gardeners” and the evolving shifts in thought and management, were the most interesting part of the book.

The history of botanical gardens has similar arc. So much so that when the Ecological Society of America was formed in 1915 and one of its first acts was to, “express concern about the competing roles of national parks as tourist resorts and nature refuges, which, they said, had gravitated far more to accommodating visitors than preserving a biological legacy,” it could have been speaking about the traditional roles of botanical gardens as institutions of science, learning and conservation; and the current trend toward non-botanical/horticultural event venues and being pleasure parks.

Smith writes in a style and pacing familiar to readers of The New Yorker long form. He moves smoothly from essay to science writing to historical journalism and trial reportage. Through it all the Engineering Eden is a sobering look at a history that is seldom told and little known. It’s probably no accident that it debuts in the 100th anniversary year of the national park service. Hopefully the story will not be lost in the celebration.

At the end of the day, national parks ARE gardens. When Starker Leopold spoke to the Sierra Club’s Fourth Biennial Wilderness Conference in 1955 he said that wilderness areas should be managed, “to simulate original conditions as closely as possible.” (emphasis added). Smith unpacks that statement in a thought-provoking and critical way, stressing the difference between a simulation or “approximation” and “precise re-creation .” Tellingly, he writes, “…a simulation had a maker. It was not a thing in itself, but rather the product of an intention in the maker for the benefit of a viewer or user...” (emphasis added).

What Smith has just done is provide a clear and unambiguous definition of, “garden.” And Leopold’s point was that to be a guardian, you have to be a gardener.

An entire public sector bureaucracy has mushroomed to deal with our national open spaces, the resources they contain, and the conservation of the life forms and processes that inhabit them. There is no going back. By as early as the 1920’s the “balance of nature” was irretrievably broken, and now some of the elements needed to even approximate pre-settlement conditions are gone and not coming back. Smith concludes that the big questions haven’t been answered…and he argues they shouldn’t–so they get asked and discussed every time we face a decision about preserving life on earth.

The big questions playing out in our gardens are likewise unanswered. Too often they aren’t even asked. The big take-away from Engineering Eden is that they should be–and honest, respectful discussion should ensue—every time we confront decisions to be made in our most precious spaces.

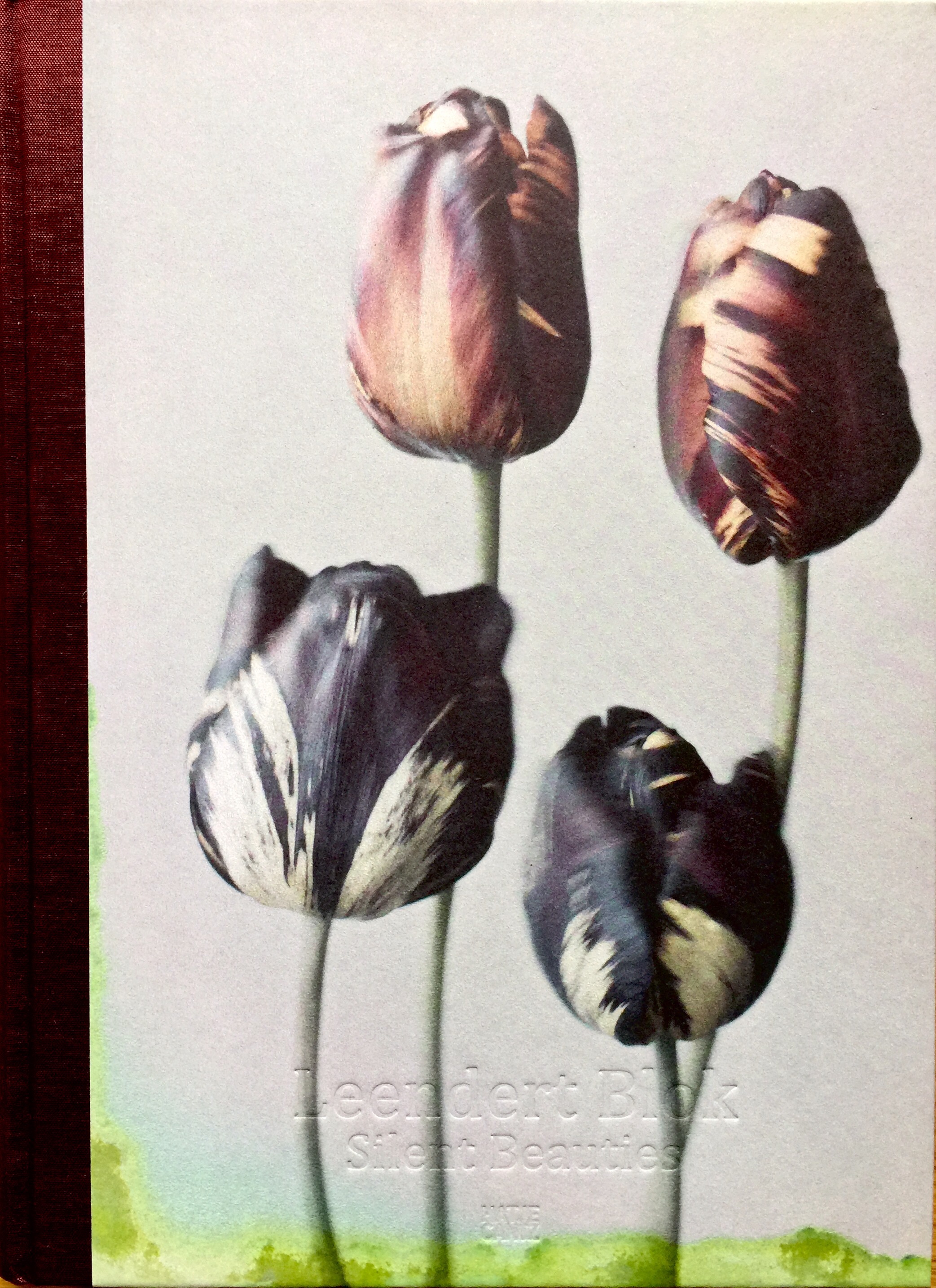

Leendert Blok: Silent Beauties–Photographs from the 1920’s

A photograph of a plant always contains a message.

–Gilles Clément (from the text)

If Clément’s statement is true, then the central message of Leendert Blok: Silent Beauties–Photographs from the 1920’s (Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, Germany, 2015) is, “We were there….”

The book examines the nascent color work of Blok (1895-1986), an early adopter of the Lumières’ Autochrome process, one of the first uses of color in photography—and the dominant process before the invention of color film. Mssr. Clément’s too-brief text and the ethereal photographs of Leendert Blok provide a fascinating glimpse of the intersection of the histories of photography and horticulture and evidence that, though unrelated, the two disciplines were advancing at the same time and grew up benefiting from each other.

It was serendipitous that color photography was developed at the same time that horticulturists began addressing market demand by developing varieties never seen in nature—large, colorful flowers resulting from plants being “manufactured” and controlled in careful breeding programs. At the same time the plant world was making plants with big, technicolor flowers the industry’s dominant paradigm, photography was venturing into the world of reproducing subjects IN color. For Blok it was a marriage made in heaven.

The link between the histories of photography and of horticulture runs deeper than Blok’s work. One of the very first books to feature color photography and color printing was, Luther Burbank: His Methods and Discoveries, Their Practical Application. This twelve volume magnum opus is the most extensive publication of the renowned horticulturist Luther Burbank (1849–1926). The set, published in 1914-1915 contains 1260 photographs from autochrome plates.

One hundred years later, this book is the first to feature Blok’s work. During his career, his main clients were nurseries and bulb producers who used his images as catalogue visuals and marketing pieces.

Clément assumes that Blok was aware of the work of Karl Blossfeldt, (see, Karl Blossfeldt: The Complete Published Work (Hans Christian Adam, Taschen: 2008)) a contemporary who blossomed into public consciousness in his sixties after decades of using his work as teaching aids. There is no indication that the two were acquainted. Or that either knew Burbank…though they may have known his work.

As opposed to Blossfeldt, who built his own cameras to photograph the minutiae of plants– leaves, tendrils, leaf scars, cross-sections, apical stems, fern croziers, but less frequently flowers—Blok’s photographs are almost exclusively of the blooms created by horticulture.

The book showcases plates made in the 1920’s and —the pre-film portion of Blok’s career. The plates gain a measure of their appeal from the process used to create them. They carry the patina of age and their color has held well. The autochrome process was technically demanding and required slow shutter speeds. Prints tend to be grainy, giving them what has been described as “a hazy, pointillist effect.” The result is a dream-like quality still popular today—as evidenced by dozens of smart phone apps with filters to emulate the same effect.

The text by Clément focuses on Blok’s subjects, the “Silent Beauties” of the title. Between it and the very short biography of Blok, there is relatively little mention made of career (which after all spanned a far longer period than that covered by the book) and technique. More on each subject would have been welcomed.

That Blok, like Blossfeldt, was not appreciated as an artist early on is understandable as his photography was done with commerce, rather than art, in mind. The rediscovery of his oeuvre and the publishing of this early portion of it exposes his efforts to the light of day and should ensure his spot in the history of photography—and add to the lore of man’s involvement with plants.

Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Western Mediterranean

There can be no disputing that the western Mediterranean is one of the most desirable travel locations in the world. Pick a country and tourism is likely to be one of the biggest drivers of its economic engine. But a hidden wonder awaits, if only people would budge from their sun-drenched beaches, boats, cafes, shopping and museums. Though the countryside is one of the most human-impacted on earth, it retains an incredibly rich and diverse flora with many plants that can be found nowhere else.

Plumbing the depths of this treasure trove is a task that requires help and guidance. Once past the “plants as backdrop” stage, the naming of its members takes on an addictive appeal. Chris Thorogood’s Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Western Mediterranean (Kew Publishing, 2016; 640pp;. ISBN 9781842466162; Hardback) is calculated to give readers the best chance identify plants they might encounter in the region.

The flora of Europe and northern Africa is vast, particularly so in the mediterranean climate belt surrounding the great sea. This is the first time that the phytogeographic region of the western mediterranean is covered.

Thorogood, quickly becoming a 21st century Oleg Polunin, published a Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Algarve with Simon Hiscock just two years ago, here splits his consideration of eastern and western Mediterranean based on climate (which in this volume is the classic hot, dry summer/cool, wet winter we think of as “the” Mediterranean climate) and hints that a separate guide should be published for the East.

Certain classes of plants are separated from consideration here to help make the job manageable. Alpines, the flora of Macaronesia, and the mountain and desert zones of northern Africa are left for another day and other books. As it is the book covers 2400+ of the species you’re most likely to encounter—along with a tantalizing sprinkling of endemics and local rarities to keep you life-listing past your first trip to the area.

The book is a visual treat with over 1400 record photographs taken in situ and in excess of 880 line drawings to emphasis details helpful to identification in the field. This makes it a treat for the old-school, morphologically-minded amongst us, but a big nod is given to the growing importance of genetic analysis in the classification of plants as the entire volume is laid out in accordance with relationships established by the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (which published its fourth major iteration just this month in the Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society). Taxonomy is a moving target and readers may, consequently, encounter names with which they are unfamiliar. Including synonyms helps tie up any loose ends that may otherwise frustrate.

The bulk of the book, as is to be expected, is made up of species accounts. These are consistent with Thorogood’s prior work, and will be familiar to anyone who has experience with well done field guides. Accounts include native plants and exotics that have naturalized (e.g. the genus Agave and members of the Cactaceae family, which are seen across the region and thought by many to be native).

Don’t just flip to this section and put the book on the shelf or in a rucksack (though it’s a hefty book to put on your back!). The first 40 or so pages are packed with useful information to read before you strap on your boots. Thorogood does an wonderful job of clearly explaining classification and identification of plants, geography—pointing out great places to see wildflowers (your bucket list is going to grow…), and explaining wild flower habitats, including agricultural and disturbed lands.

No field guide is complete or perfect. Some will complain that Thorogood omits keys. His introductory pages, however, include many notate bene. This is clearly done to establish expectations, to tell readers what the book is and what it isn’t; what it contains, and what it leaves out. It’s another reason that it’s important to read these pages. On the issue of dichotomous keys for identifying plants he notes that for most people they are too much information, difficult for non-botanists to use properly and can lead to confusion.

The author is unapologetic about his extensive section on the Orobanchaceae, where you will find many species seen only in the most local floras. It is a treat, as his PhD had the biology of parasitic plants as its subject and he knows this material as well as anyone. As an aside, the family contains some of the most beautiful flowering plants you’ve never seen.

Thorogood’s guide is rigorous and easy to use. Not just a field guide, the book will appeal to gardeners—and not just those in Mediterranean climates. It may surprise readers to see both common and uncommon species that tolerate more temperate continental climate like that of the US northeast (e.g. the Helicodiceros about to bloom in my NJ garden hails from Sardinia and Corsica, yet has persisted here for years). I’ll leave it to you to find your favorites.

There are many field guides to the wild flowers of the Mediterranean. Most cover such a wide area with vastly different climates that they cannot hope to match the breadth of Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of the Western Mediterranean. One can only hope that the whisper of a similar work for the eastern region will be brought to fruition.

The High Line (Phaidon Press, 2015)

Two inches…

You need to make two inches of space on your groaning shelves to house The High Line (James Corner Field Operations, Diller, Scofidio + Renfro; Phaidon Press Inc.; New York, 2015; 452pp,; $75.00). Better yet, leave it out as evidence of your refinement and good taste, and a sure-fire conversation starter.

In its short life, the High Line—park, garden, promenade, mile-and-a-half short cut over the streets—has become an icon, its predecessors nearly forgotten as it spawns imitations and adaptations across the globe.

This beautiful book is a must-own for lovers of the park, urban renewal and gentrification (in the best sense of the word). In an amazing look “under-the-mulch” at the development of the concept, planning, design and construction of the High Line, its designers put it all on the line, sparing no secrets and adding more spice to the improbable tale of the resurrection of a feral landscape floating 30 feet above the city.

Phaidon has delivered a fine example of the book-maker’s art. The High Line has even higher production value than their offering of last year, the monumental The Gardener’s Garden. One miss was the separation of extended captions for an entire archive of historical material—necessitating continuous flipping back and forth to capture background. In light of the overall effort it’s a minor inconvenience. Beautifully put together, the physical book complements the material it contains and the care that went into designing it.

Densely visual, this five-and-a-half pounder is packed with photographs, maps, plans, construction documents and specifications, and planting plans. Many are foldout and, with the already horizontal orientation of the book, echo the narrow layout of the park itself.

It’s organized chronologically and catalogs its riches from the days before the idea of the High Line arose through planning, construction and use. Its life as a railway from 1934 to the last train in 1980 is not ignored, but it is with the creation of the Friends of the High Line in 1999 that things begin to take off. A 2004 design competition (won by the authors) starts the history of the project. This and the design process in 2005 mark the most interesting material in the book. Photographs detailing the construction process from 2006 through its three staged opening (2009, 2011, 2014) provide an incredible historical archive. It closes with reflections and observations, some expected, some not, now that the entire length of the project is open and ten years elapsed.

Light on text, its most interesting material for some will be the 28 pages of transcribed discussion—divided into three parts—between the design principals, Elizabeth Diller, James Corner, Ricardo Scofidio, Lisa Switkin and Matthew Johnson. Their personal thoughts and reflections enrich the book as they did the project. Inspired by the feral nature of the structure they encountered, they embraced a ‘keep it simple, keep it real’ mantra that belies the complications they faced. In some ways the repartee in these too few pages is more revealing than the eye-candy—a fascinating look into the designer’s mind and process. A true inside look at their work from concept, to process and through execution. It is an apt accounting of what Diller calls, “…the obsolescence of one program stimulating the invention of another…”. To round out your High Line library, put this book next to High Line: The Inside Story of New York City’s Park in the Sky, by Joshua David and Robert Hammond, founders of the Friends of the High Line. The two together provide the definitive, first-person accounts of the High Line from its creators and designers.

The High Line is a celebration of a project, “the process is the thing” thinking—and a refutation of Picasso’s famous saying, “Every act of creation is first of all an act of destruction.” It might have been easier to pull the structure down and start with a blank slate. What a shame it would have been. Instead the concept of repurposing post-industrial structures rather than erasing the past has inspired urban planners around the world. Millions of visitors a year validate the decision to celebrate what has gone before and give it new life for years to come.

Recent Comments